Elizabeth Ames, Vice President of Marketing and Alliances for the Anita Borg Institute began her Tuesday SXSW Interactive panel by presenting a date to the audience.

Elizabeth Ames, Vice President of Marketing and Alliances for the Anita Borg Institute began her Tuesday SXSW Interactive panel by presenting a date to the audience.

May 28, 2014.

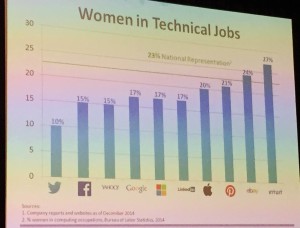

Though most people may not recognize the date, she cites it as an important turning point in the struggle of women in STEM fields. On that day Google decided to publish, publicly, the breakdown of their workforce in terms of gender and diversity.

Though most people may not recognize the date, she cites it as an important turning point in the struggle of women in STEM fields. On that day Google decided to publish, publicly, the breakdown of their workforce in terms of gender and diversity.

Most companies will publish this information when they go public but more often than not it’s buried somewhere on their website, meant to be technically accessible but not advertised. For a company as large as Google to publicly address the issue, say “this is where we are” and commit to change was a huge change in the industry and forced many other companies to do the same or be seen as behind the times, Ames told the audience.

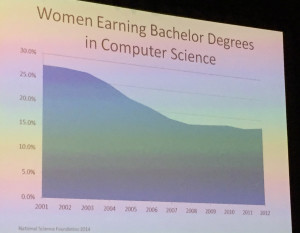

She gave a brief breakdown of the current situation for women in STEM fields. Strangely, as computer science has become a more necessary skill women have become less and less likely to go into the field. In 2001, 25% of Computer Science degrees conferred were to women graduates. This was already down from close to 40% in the eighties. In 2012, the number had slipped to 18.2%

She gave a brief breakdown of the current situation for women in STEM fields. Strangely, as computer science has become a more necessary skill women have become less and less likely to go into the field. In 2001, 25% of Computer Science degrees conferred were to women graduates. This was already down from close to 40% in the eighties. In 2012, the number had slipped to 18.2%

The most common excuse for why women aren’t being hired into the tech workforce is that there’s a “pipeline issue,” meaning enough women aren’t getting degrees in the requisite fields and this means they won’t be as large a percentage of the working population.

Ames believes that there’s actually a chicken-and-egg situation at play wherein this pipeline problem continues throughout women’s careers and might actually be operating in reverse. She thinks a lack of professional female role models and witnessed demoralization at higher levels discourages young women from going into these fields.

She spoke about research done in the area of unconscious biases employers and recruiters hold. An experiment was conducted where the same resume was sent out to hiring managers throughout a city. When the resume was under the name “Brian Miller,” it was kept for the second round of questions 79% of the time. When the exact same resume was sent out with the name “Karen Miller,” it was only kept 49% of the time.

A second experiment asked recruiters to decide whether education or experience would be the deciding factor for their position. In this instance they chose education. They were then shown two resumes, one with more education and the name Brian Miller, another with more experience and the name Karen Miller. They were consistent to their decision and chose the resume with more education; Brian’s resume. However, in a second instance, when they were shown a resume with more experience and a male name, and a resume detailing the extra education they had asked for under a female name, they shifted their criteria and ended up choosing the resume with more experience; again the male-named resume.

She also detailed an experiment where comparisons were made between a quiet, humble man and woman and a second set that were more verbal about their accomplishments and skill sets. While both the man and woman who were verbal about their accomplishments were perceived as more competent, the woman was also seen as less likable.

This led into Ames sharing the fact that the number one reason women cite for leaving technical professions is lack of promotion.

It is precisely this culture that is discouraging women from entering fields like Computer Science, not the fact that there just aren’t enough women for jobs that would be fairly given to them, she said.

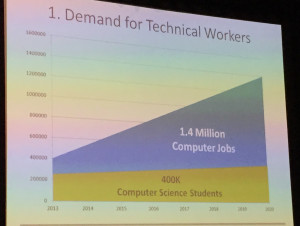

A reason, outside the fact that it’s the right and good thing to do, that this is important, Ames added, is that this field is growing exponentially and we need more people for these jobs. The industry, she said, cannot afford to ignore half of the intellectual capital the country has to offer.

A reason, outside the fact that it’s the right and good thing to do, that this is important, Ames added, is that this field is growing exponentially and we need more people for these jobs. The industry, she said, cannot afford to ignore half of the intellectual capital the country has to offer.

The commitment to change these patterns must come from the top, Ames said, and there must be systems in place to measure progress, assess accountability, and reexamine processes and systems to remove existing barriers.

She left the audience with a quote from Megan Smith, the CTO for the US government, which she said perfectly illustrated that the issue was not about blame and shouldn’t inspire defensive reactions.

“Recognize that we didn’t create this problem but we CAN fix it.”